INTRODUCTION

One of the few artistic

and beautiful styles of pottery decoration of the

nineteenth century ' This was how William Burton, a

leading turn-of-the-century potter, distinguished writer

on ceramics, and manager of Pilkington's Lancastrian

Pottery described pate-sur-pate in the 1910 edition of

the Encyclopaedia Britannia '

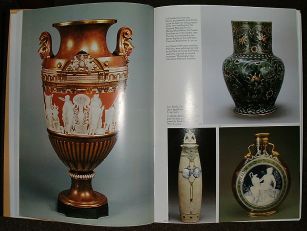

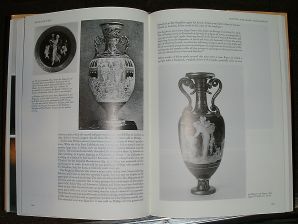

Pate-sur-pate -fate was an elaboiate and expensive method

of decorating porcelain in which a translucent cameo-like

image was built up by the application of many thin coats

of porcellaneous slip The technique was developed at the

end of the 1840s at the French national manufactory of

Sevres and greatly refined over the next ten years,

notably by Leopold Jules Gely and by the man who would

later be internationally celebrated as the greatest of

all pate-sur-pate artists. Marc Louis Solon, master of a

method he evolved over half a century

It was Solon who introduced the technique to England when

in 1870 at the time of the Franco Prussian war he left

Sevres to join Minton in Stoke-on-Trent Other

manufacturers in France, followed by those in Britain,

Germany, Russia, Italy, and Hungary, soon recognized the

decorative potential of. pate-sur-pate, which reached its

fullest and most widespread realization in the last

quarter of the nineteenth century Individual pieces and

displays drew interested comment whenever they were

included in international exhibitions In the USA, museums

and patrons acquired examples of the admired decoration

from exhibitors at Vienna and Philadelphia in the 1870s

the method itself was brought over by English artists in

the 1890s and later the eminent French ceramist Taxile

Doat made and taught pate-sur-pate for four years at

University City, Missouri, but production of the ware in

the USA was not extensive The twentieth century saw a

gradual decline in the manufacture of pate-sur-pate,

mainly on grounds of cost Sevres had probably ceased to

make it by 1930 Minton maintained output, although much

reduced, until the outbreak of World War II, when their

one re~ maming pate-sur-pate artist, Richard Bradbury,

left for military service In the post-1945 period two

attempts have been made to revive the process at Minton

using Solon's accounts as a guide Failing initially in

their efforts to get successive coats of slip to adhere,

the firm succeeded in 1991 in producing two handsome

vases to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Minton's

foundation in 1793. Historical precedents for ornamental

relief decoration were of two kinds antique stone cameos

and cameo glass in which a raised and carved upper layer

was set in relief against, and often revealed, a

different coloured ground, an effect imitated in the late

eighteenth century both by Josiah Wedgwood on his

jasper-ware medallions and plaques, and by Sevies in

biscuit porcelain, and the white painted decoration on

Limoges enamels which again relied for its effect on the

contrast between design and coloured ground However Solon

in an article written for The Studio in 1894, was at

pains to distinguish the quality of pate-sur-pate pate

from other methods of decoration with which it was compared:

The Wedgwood Jasper

ware, for instance, although offering likewise white

reliefs on coloured grounds, is as the reader is no doubt

well aware, produced by mechanical means Each part of a

given model is pressed separately in a plaster mould and

sub sequently stuck on the even surface of the piece to

be decorated It may be multiplied to an unlimited number

of copies, a careful workman is equal to the task A Pate

sur Pate bas relief, on the contrary, is always an

original, a repetition of it could only be made by the

artist who has executed the first one In the Limoges

enamels sometimes mentioned as presenting some analogy,

the difference is still better marked, for in this case

effect is not obtained by gradation of reliefs, but

rather of lights and shades The dark tint of the ground

is taken advantage of to form the shadows, and the white

enamel comes into play, just as white chalk intervenes in an

effective drawing on tinted paper.

The immediate inspiration ior pate sur-pate was in fact

provided by none of these sources The technique developed

at Sevres followed speculation about the in method used

to produce the raised white flowers on a Chinese celadon

vase the ceramics museum there These flowers were wrongly

thought to be translu- cent, and trials were carried out

to produce a similar decoiation . Success was achieved in

1849 when a sucrier decorated with raised insects

ornaments emerged from the kiln with the celadon ground

colour clearly visible through the decoration,

The subsequent application of the technique focused on

what Solon called "The successful management of those

transparencies". Great care and calculation was

required, as William Burton's account, relying on Solon's

own method, shows: As practised by M. Solon the

pate-sur-pate decoration took the form of paintings of

figure subjects or dainty ornamental designs in white

slip on a coloured porcelain ground of green, blue,

dark-grey or. black. On such grounds a thin wash of the

slip gives a translucent film, so that by washing on or

building up successive layers of slip sharpening the

drawing with modelling tools, or softening or rounding

the figure with a wet brush, the most delicate gradations

of tint can be obtained, from the brilliant white of the

slip to the full depth of the ground. This method was

rapidly adopted by all the principal European factories,

though nowhere was it carried to such perfection as at

Sevres and at Milton's. M. Taxile Doat has executed

extraordinary pieces in this style of decoration at

Sevres, and in the British Museum there is a large vase

of his, presented by the French government at the

beginning of the present century Sevres made no secret of

the technique and Victor de Luynes, a professor at the

Pans Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers, included an

account of it (reproduced in Appendix A) in his report on

the 1872 London International Exhibition' Solon also

described his working methods, first in a general

article, already quoted, in The Studio, later reissued by

Minton as a booklet, and again in the Art Journal in 1901

A concise account of the process, again written by Solon,

appealed in 1896 as a 'special contribution' in Rough

Notes on Pottery, a US publication Amongst the various

styles of decoration which the artist may borrow from the

potter, the process of Pate-sur-pate stands alone with

regard to the peculiar effects that may be obtained from

it Wedgwood's jasper reliefs are the nearest approach,

but the figures and the ornamentation with which jasper

ware is adorned, are all pressed in moulds, and simply

stuck on the surface The result is a work, which how ever

skilful in treatment, does not go beyond the refined

productions of a superior handicraft It is not so with

the Pate-sur-pate process A plain piece, made of a

porcelain body, coloured with metallic oxides, and still

in the clay State (that is to say, before it has"

been submitted to any firing) is taken in hand by the

artist Freely he sketches upon a subject of ( his own imagination The white porcelain

clay, diluted with water to consistency of batter, or, as

it is called, the 'slip', serves to produce the reliefs.

By means of a painting brush the slip is laid upon the

piece by successive coats care being taken to wait until

the coat is perfectly dry before applying another.

Failing that precaution the raised work might crack and

peel off Thus, by degrees, the reliefs attain respective

thicknesses They are then worked into with sharp iron

tools which scrape and smooth the inequalities of the

rough sketch, incise the details and delineate the

outlines, whilst the brush loaded with thicker slip,

brightens the whole work with sharply raised touches When

the piece is considered as completed and reach for the

oven, it is, from beginning to end, the original

production of the artist's hand.

But it is only through the action of the fire, which

causes the incipient state of vitrification of the mass,

that the translucency of certain parts will become

apparent when at work the artist has no means of

ascertaining the degree of transparency that the firing

will develop, he can only depend on his experience and

judgement All ends often in disappointment, for after the

piece has passed through the oven, to retrieve any

mistake, or to amend any accident has become an

impossibility One may rest satisfied if the fruit of a

long labor does not come from the firing split into

fragments, disfigured by unseemly blisters, in short, an

altogether worthless wreck Decoration in colored clays

are applied in the same manner The various colors are

obtained by mixing with the porcelain body, given

quantities of oxide of cobalt, chromium, iron, uranium,

titanium, and other metalloids These mixtures have to be

artfully compounded in such a way that the contraction

they undergo in the firing shall be equal in all cases.

In his Cantor Lecture delivered to the Society of Arts in

January 1881, the cera-mist Professor A H Church has left

an eye-witness impression of Solon 's working method,

which corroborated Solon's own technical account of his

procedure Church remarked 'It is marvellous to see Mr

Solon, as I have been privileged to see him, without

outlines or previous sketching, laying the wet

por-cellanous slip with a brush on the coloured ware in

the green state, and then carving the powdery substance

into forms of exquisite truth and tenderness' Although

these accounts suggest that the clay was not submitted to

any firing before work on it started, this was not

strictly correct To make the material easier to handle,

it might be passed through a low-fired hardening kiln The

point was made by Solon himself in The Studio and by

Frederick Alfred Rhead, who in 1513 contributed three

articles on the subject to the American magazine Keramic

Studio, summarized in Appendix B Rhead had been a pupil

of Solon at Minton, and retained a lifelong enthusiasm

for pate-sur-pate Neither Solon nor Rhead stated how many

coats of slip were necessary to build up the required re

lief, relying, no doubt, on experience and artistic

judgement The French ceramist Theodore Deck, writing

during his time as administrator of the Sevres

manufactory, was more specific, observing that thirty or

forty coats were usual, and that for this reason the

process was far too time-consuming

The reward for the artist of this lengthy procedure lay

in the charming effects that could be achieved by

manipulating thicker and thinner reliefs The translucent

quality of the medium could be used to virtuoso effect in

suggesting distance and in the realistic rendering of

clouds, water, and diaphanous drapery which revealed the

form of the human body, particularly the female figure

Transparent effects of this kind made great demands on

the skill of the pate-sur-pate artist, as Solon made

clear, and they were the feature most admired by

contemporaries, among them Leon Arnoux, Minton's art

director The subtleties of the process could be further

enhanced by the use of delicate tones, one of which

reminded the an critic Philippe Burty of a 'nuage de

creme verse dans une tasse de the' Pate-sur-pate was the

description originally given to the technique at the

Sevres manufactory, but variations on this terminology

were soon introduced These included pate d'application,

pate rapportee, and sometimes pate blanche or pate

coloree The last term referred to decorations with

coloured paste, which were applied, as Solon explained in

his contribution to Rough Notes on Pottery, the same way In the 1860s Arnoux

described the technique as pate-sur-pate in his

exhibition reports and was probably the first person to

introduce, the term to England

Barbotine was another term used in France, particularly

in Limoges Derived from the Old French bourbe, meaning

mud or clay, barbotine can be translated as 'slip' or

liquid clay, and was used by de Luynes in this sense in

his description of pate-sur-pate quoted in Appendix A

Confusingly, it was also the name given to a decorative

process unconnected with pate-sur-pate, referring to a

method of painting with slip on earthenware developed in

the early 1870s by Ernest Cha plet Solon included a

description of this successful, but short lived, process

in his account of the revival of French faience

'Barbotine painting' 'consisted in mixing fusible colours

with clay and opaque substances, so that they could be

employed in any degree of thickness, the sharpness of the

artist's touch was not impaired by the firing, when

completed, the work had the appearance of an oil

painting' In 1873 the Limoges firm of Haviland opened an

atelier in Pans Auteuil which made work of this type, and

other manufacturers were quick to follow suit The

popularity of barbotme painting lasted for only a few

years an the Auteuil studio closed in 1882 In Limoges,

presumably because of the Havi-land connection, the name

barbotme seems to have been used indiscriminately to

describe either Auteil-type barbotine or pate-sur -pate

When the term barboine appears in Limoges exhibition

catalogues, the imprecise terminology means that it is

not always possible to deteimme which product is being

refferd to. This Problem is discussed again in the

section in chapter 3 on the Limoges; Potteries To add to

the confusion, barbotine is used today as a generic term

for majolica.

In Britain the technique has commonly been described as

pate-sur-pate since its introduction The literal

translation, paste-on-paste, sometimes used in English

and American publications, is both misleading and

inappropriate as it can apply equally to other

techniques, among them slip-trailing and tube-lining From

March 1878 until the end of September 1883 the Minton

records refer to 'M S P', the 'Minton Solon Process',

rather than pate-sur-pate Although no obvious change can

be detected in the appearance of the work, the initials

may have been adopted as a patent to differentiate

Solon's procedure from that of several other English

manufacturers who were making pate-sur-pate at die time

Elsewhere in Europe, pate-sur-pate was the accepted name

for the process, used tor example at Meissen and KPM

Berlin, though German journalists sometimes referred to

Pinselmalerei The firm of Villeroy & Boch is an

exception and made at its Mettlach works a range named

Phanolith, in which plaques and other subjects were

decorated in a manner similar to pate-sur-pate In the

USA, too, pate-sur-pate was the term in general use.

During the second half of the nineteenth century and the

first quarter of the twentieth, pate-sur-pate,

paiticularly the work of Solon and Taxile Doat, was much

admired.

The designer Lewis F Day, for instance, thought the

tianspa-rency and modelling of Solon's work 'one of the

most beautiful of modern times', while William Burton

placed it in 'the post of honour among the artistic

productions of the nineteenth century' Museum curators,

too, were equally enthusiastic Edwin Atlee Barber, the

leading American ceramic historian at the time and

curator of the Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, wrote

of 'this beautiful art', while Bernard Rackham, keeper of

ceramics at the Victoria & Albert Museum, regarded

Solon's work 'as amongst the best things of the ceramic

art of the 19th century' The British Museum's keeper of

ceramics, R L Hodson, observed 'Mr Solon made no secret

of his art Every stage of his procedure was clearly

explained One could borrow everything from him

-everything except the one thing most needful - the touch

of his peculiar genius in the ceramic history of the

nineteenth century few names would stand out in higher

relief than that of the master of pate-sur-pate After

World War I pate-sur-pate, like most nineteenth-century

fashions, declined in populanty 'Writing in 1940 in A

Potter's Book, Bernard Leach observed sourly: 'It would

be difficult to find a better example of what should not

be done with clay' Today Solon's elegant works, and those

of the many other talented artists who practised the

technique, are once more appreciated for the skill and

beauty of their achievement.

|